The Future Papers, Part One: Cunningham & Noys

As promised, we present here the first in a short selection of transcriptions of talks from the recent series on ‘The Future’ at the David Roberts Art Foundation. In the following post we have David Cunningham’s introduction to the series along with Ben Noys’s Ballard paper (which can be found up on his own blog). Further papers by Stephen Melville and Garin Dowd will be posted soon. Enjoy.

1. ‘Introduction: The Tomorrow That Never Was’

David Cunningham

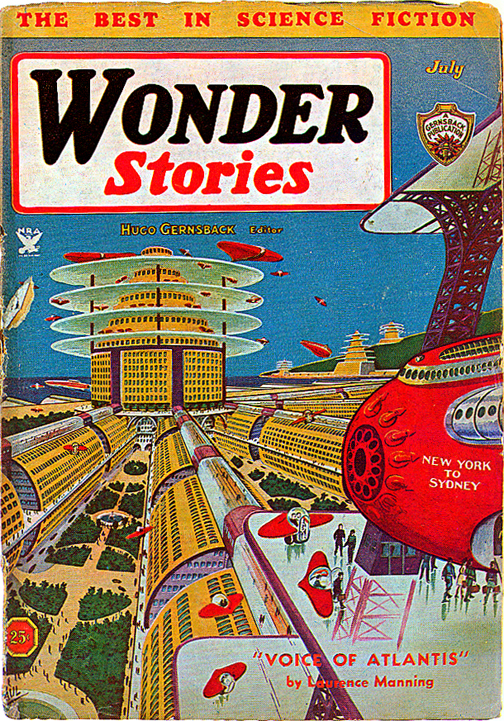

I want to begin with a short story by the writer William Gibson, entitled ‘The Gernsback Continuum’ and published in 1981. You can read it here. In the story, Gibson’s narrator (a hack photographer) is engaged to work on an illustrated history of ‘American Streamlined Moderne’, with the working title The Airstream Futuropolis: The Tomorrow That Never Was: ‘“Think of it … as a kind of alternate America: a 1980 that never happened. An architecture of broken dreams”,’ one of the story’s characters tells him. ‘And as I moved among these secret ruins’, the narrator continues, ‘I found myself wondering what the inhabitants of that lost future would think of the world I lived in.’ Thus progressively propelled into a state of half-paranoiac and half-melancholic delirium, accompanied by hallucinations of a ‘dream Tucson thrown up out of the collective yearning of an era’ – a city ‘soaring up through an architect’s perfect clouds to zeppelin docks and mad neon spires’ – the narrator is only finally returned to the sanity of the present by an immersion in the very seediest aspects of a very contemporary reality.

Gibson’s vision of a ‘lost future’ – ‘segments of a dreamworld, abandoned in the uncaring present’ – is drawn from the imaginary of popular science fiction. Yet it speaks too, I think, to a certain aspect of our relation to modern art and culture far more generally. Certainly it is in this regard that it might be placed alongside the current exhibition, Sculpture of The Space Age, the title of which itself refers to a short story – in this case, J. G. Ballard’s ‘The Object of the Attack’ – and to a purely fictional exhibition which is described as having been held at the Serpentine gallery in the late 1970’s within its pages. Let me quote the show’s curator Raimundas Malasauskas : ‘Sculpture of The Space Age became an anachronism that keeps living on its own ambivalence as something that could have happened, then almost happened again. It openly contains its own possibility and impossibility. … The show looks as if it was installed in the 70s, but will open its door only tomorrow’. Such a conception of the ‘anachronism that keeps living on its own ambivalence as something that could have happened’ seems, neatly, then to tap into a more general aspect of the zeitgeist concerning the contemporary’s relation to the future – one which, at the beginning of the 1980s, Gibson’s short story already reflects. This is a future understood less in terms of that radical creation-through-destruction that would open up the future as a horizon of expectation or anticipation – as it was, say, both for the early 20th century cultural and political avant-gardes and for many of the writers and filmmakers of popular science fiction’s golden age – than as itself a temporal phenomenon that is to be located, today, within the past itself, and which can only be accessed via some kind of nostalgia for, or archaeological recovery of, ‘the future’ per se: a journey through its ruins.

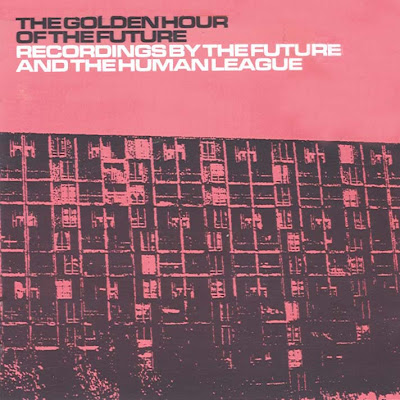

It is fair to say that much art of the last decade or so has had its face squarely turned towards the past, preoccupied, as it has been, with forms of history, cultural memory, and the archive. But as Shumon Basar points out: ‘Memories and nostalgia are no longer the sole province of the past – the future is just as susceptible to our longing, heart-breaking laments’. As such, a new and distinctive concern with art’s ability to engage the future is apparent within this very turn to cultural memory and the archive as well. Indeed, as the title of one recent piece by the Austrian artist Dorothee Golz would have it, the fascination with the past is, for many artists and writers today, clearly itself a ‘looking back to the future’, which can – such works would often seem to say – now only be located and recovered retrospectively (whether in the early twentieth-century avant-gardes or in the stylised utopias of a cold war modern or in the electric dreams of late 1970s and early 1980s synth pop).

There are some obvious reasons for this. Modernity is hardly our antiquity, as some have claimed – a basic category mistake, if ever there was one – yet it is undeniably the case that as inhabitants of the twenty-first century we live among a proliferating number of ruins of at least certain ideas and images of the modern, and of the futures that they promised. Unsurprisingly, then, as an era – in the European and North American ‘west’ at any rate – ours seems most obsessed with the energies contained in those futures that precisely never happened, that failed ever to arrive. (This is perhaps one reason, for example, why Walter Benjamin – fixated, as he was, in the years leading up to the Second World War, on the latent utopias and stalled alternative futures of modernity’s own nineteenth-century history – should be the patron saint of so much contemporary theory.) By contrast, for most early twentieth-century avant-gardes, in the words of one Russian movement, it could be taken for granted that, in the most direct of fashions: ‘The future is our only goal’. This was a future that was near visible, on its way, just over the horizon. Perhaps most importantly, it was in such an opening to the future – in its capacity to propel itself towards it – that art’s potential for politicisation was located, from the avant-gardes of Russian Constructivism to Surrealism and beyond. (Indeed, post-Burger, it seems to me that this is precisely the way in which we need now to re-think the concept of the avant-garde itself, as, above all, a concept of time. But that’s another story…) The Futurists, argues Julia Kristeva, ‘heard and understood the Revolution only because its present was dependent on a future’. Today, it is this that reappears, under very changed conditons, in the far more troubled responses of contemporary artists to the neoliberalist claim that ‘there is no alternative’. The apparently futural political slogan of the World Social Forums – ‘Another World is Possible’ – as, say, it was unfurled on banners, above the heads of metropolitan commuters, in a 2002 art event by the Russian Collective Radek, evidently seeks, for instance, to situate itself within a long line of speculative resistance to the ongoing repetition of the ever-same, from which art’s modernity can hardly be separated.

This is simply to say that: if the early Soviet avant-gardes immediately following the 1917 revolution – and their allies in Weimar Germany and elsewhere – felt themselves to be particularly ‘pregnant with the future’ it was, of course, because of a genuinely unique situation in which artists could truly believe that, in the words of Liubov Popova: ‘We shall build the new world’. Such hardly needs saying. Tatlin’s constructivist tower, his famous Monument to the Third International, is exemplary – all-too-exemplary – of such a kind of paradoxical early twentieth-century monument, not to a glorious past, but to the future: an expression, as Fredric Jameson puts it in another context, of ‘the demands of a collective life to come’. Yet, today, it would be hard to deny that a work such as the Monument has become a monument in quite a different way.

In fact, like the images produced by Gernsbeck’s science fiction illustrators, Tatlin’s Monument has seemed increasingly to take on an iconic historical significance, not in the power of its futural demand as such, but precisely in its being unbuilt (and perhaps unbuildable outside of the future forms of social organisation it envisaged) – thereby all-too-easily symbolising, for us, both the ultimate failure of its collective ambitions and its ongoing critical judgement upon a present in which the catastrophe is simply that ‘things’ continue to ‘go on as they are’, as Benjamin once put it. In this, perhaps, it belongs with the adult’s question directed to the once promised future of his or her childhood: ‘where is that rocket backpack that I was promised by TV?’ And like the personal rocket pack, the point about the image of Tatlin’s tower is, of course, that it precisely is a cliché of such discussions: at worst, a now useful exemplar for conservative arguments concerning the inevitable naivety and failure of all utopian impulses. A more interesting point might be that precisely as an image it is increasingly becoming more or less indistinguishable from those of popular science fiction.

That Ballard’s fictional exhibition, Sculpture of The Space Age, should be set in the 1970s seems, thus, significant in this regard – in that, retrospectively, it comes towards the very end of that era of what Reyner Banham called the Machine Age preceding our own. As in the work of Banham’s contemporaries Archigram, Gernsbeck’s blimps and zeppelins still fly benevolently here, still bringing the future in their wake.

In his memoir Miracles of Life, published in 2008, Ballard himself recalls visiting the famous 1956 exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, This is Tomorrow (also seemingly alluded to in many of the pieces in this exhibition), with which Banham, along with many others of that generation, was involved – and which helped to spawn the pop technological imaginings of Archigram, among others. Bringing together the avant-garde and popular sci-fi – in a show that included both Robbie the Robot and Marcel Duchamp – and which projected the shiny deamworlds of pop art glamour and fun, as well as the anxious look ahead of the Smithsons’s design of a ‘terminal hut’ for post-nuclear habitation, This is Tomorrow is the real ‘tomorrow that never was’ that haunts both Ballard’s later fiction and the Sculpture of The Space Age today. In its anachronism it lives on.

What, then, are we to make of this contemporary obsession with such tomorrows that never were? No doubt this rests on an ability still to distinguish between two different modalties of any looking back to the future: on the one hand, the historist-conservative modality, which would deny any future to the present and would use past ‘dreamworlds’ as a stick with which to beat any apsirations toward a better life than that of global capitalism today, and, on the other, the critical modality of an engagement with those pathologies of the present apparent in its ongoing inheritance of past futures, which would, in its acts of re-activation, seek to keep the future alive as a possibility for the present. In the nuances of this differend resides the ‘question of tomorrow’ today that both this exhibition and this series of talks seek to address.

2. ‘Better Living Through Psychopathology’

Benjamin Noys

The image of the future which I have selected is one of the series of J. G. Ballard’s pseudo-advertisements that he published in Ambit no. 33 in 1967. Ballard explains that:

Back in the late 60s I produced a series of advertisements which I placed in various publications (Ambit, New Worlds, Ark and various continental alternative magazines), doing the art work myself and arranging for the blockmaking, and then delivering the block to the particular journal just as would a commercial advertiser. Of course I was advertising my own conceptual ideas, but I wanted to do so within the formal circumstances of classic commercial advertising – I wanted ads that would look in place in Vogue, Paris Match, Newsweek, etc. To maintain the integrity of the project I paid the commercial rate for the page, even in the case of Ambit of which I was and still am prose editor. I would have liked to have branched out into Vogue and Newsweek, but cost alone stopped me … (R/S 147).

The actual image is a still from Stephen Dwoskin’s 1963 film Alone (USA 1963 13min), of a woman masturbating. The text is a typically concise and forensic manifesto for Ballard’s own counter-science fiction.

Continue reading on Ben’s blog here: http://leniency.blogspot.com/2009/11/better-living-through-psychopathology.html

Tagged as Ballard, the avant-garde, The Future

The Institute for Modern and Contemporary Culture

University of Westminster Department of English, Linguistics and Cultural Studies

32-38 Wells Street, London W1T 3UW. United Kingdom.

[…] Follow this link: The Future Papers, Part One The Institute for Modern and … […]